Major Moments In Emoji History: 1995* to 2025

Yesterday, as part of our World Emoji Day 2025 celebrations, we published a detailed history of the Twemoji emoji design set. Now, we’re discussing broader emoji history with Keith Houston, author of the newly released "Face with Tears of Joy: A Natural History of Emoji".

Earlir this week, as part of our World Emoji Day 2025 celebrations, we published a detailed history of the Twemoji emoji design set from 2014 onwards. Today, we’re turning our attention to the broader history of emojis while in conversation with Keith Houston, author of the newly released "Face with Tears of Joy: A Natural History of Emoji", in which Emojipedia research and analysis is frequently referenced. Read on to explore the evolution of emoji and find out how you can win a copy of the book.

Editor’s Note: This article is presented in a conversational format, with added context throughout and links to relevant Emojipedia articles and resources included at the end of each section.

Keith Broni: "So, what brought you to write this book about emoji? Obviously, you had blog posts, but what made you decide there was enough there to turn them into a fully-fledged book?"

Keith Houston: "It felt like I’d missed something. I’d already written books on punctuation and book history, and emoji struck me as another kind of information technology: something modern but strangely in line with those older subjects. They're not a new language, but they’re shaping existing ones in unique ways. Emoji felt like a contemporary punctuation system, and that aligned perfectly with what I’d been exploring."

Keith Broni: "And I appreciate you didn’t fall into the 'emoji are the new hieroglyphics' cliché!"

Keith Houston: [Laughs] "I’ve definitely seen that one. But no, they’re something completely different."

Win A Copy Of "Face With Tears Of Joy"

Already intrigued?

Well, if you're a resident in the United States, the United Kingdom, or Ireland, you're eligible for our competition to win one of three copies of "Face with Tears of Joy: A Natural History of Emoji" courtesy of its publisher,

If you'd like to be in with a chance to win a copy of the book, follow these two simple steps below:

- Sign up for Emojipedia's Emoji Wrap newsletter here.

- Complete the following short Google form, submitting your name, country, and email address (make sure it's the same email address as the one you've signed up to the Emoji Wrap with)

Winners will be selected next week on Wednesday, 23rd July, and contacted via email.

Pre-Emoji Days (1980s - 1995)

The earliest known visual communication systems that resemble emoji didn’t appear on smartphones: they emerged from Japan’s 1980s and early-1990s tech ecosystem.

Keith Broni: "You cover a lot of the pre-emoji landscape in your book, things like word processors and PDAs in Japan. I’m really glad you got that in."

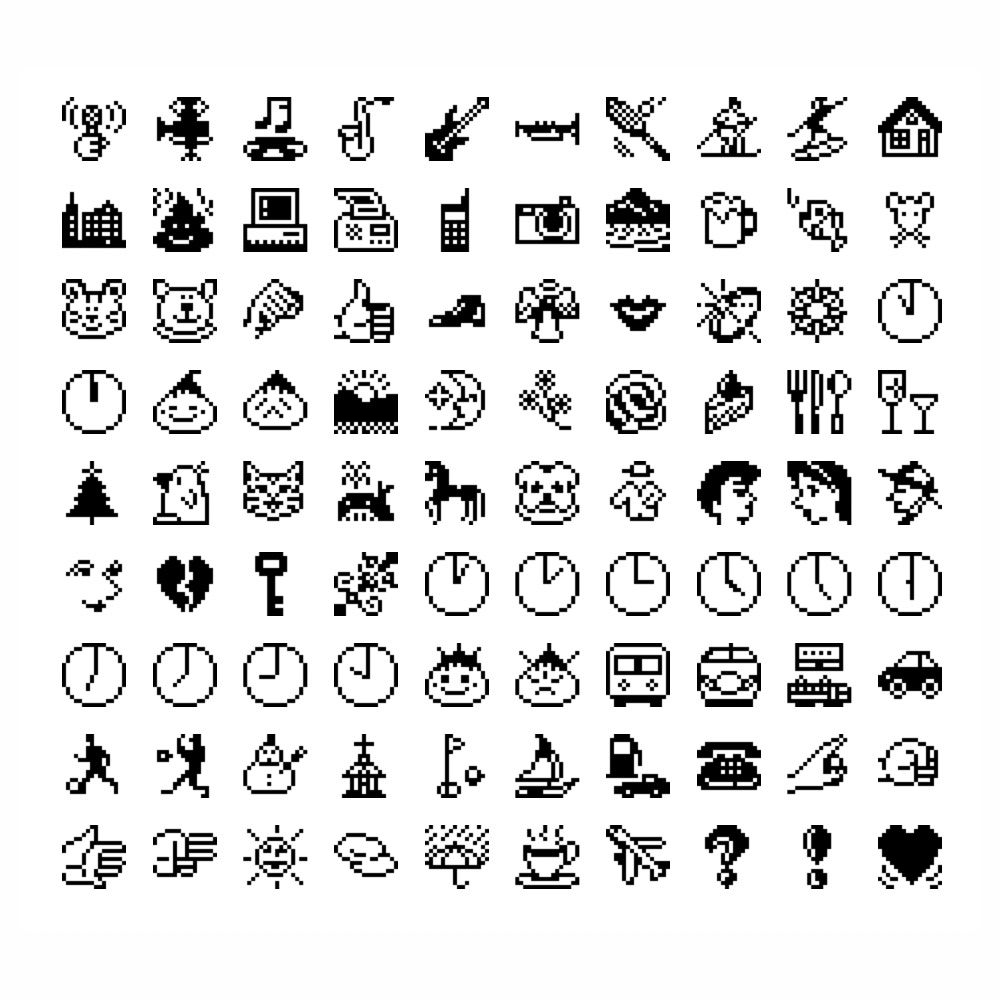

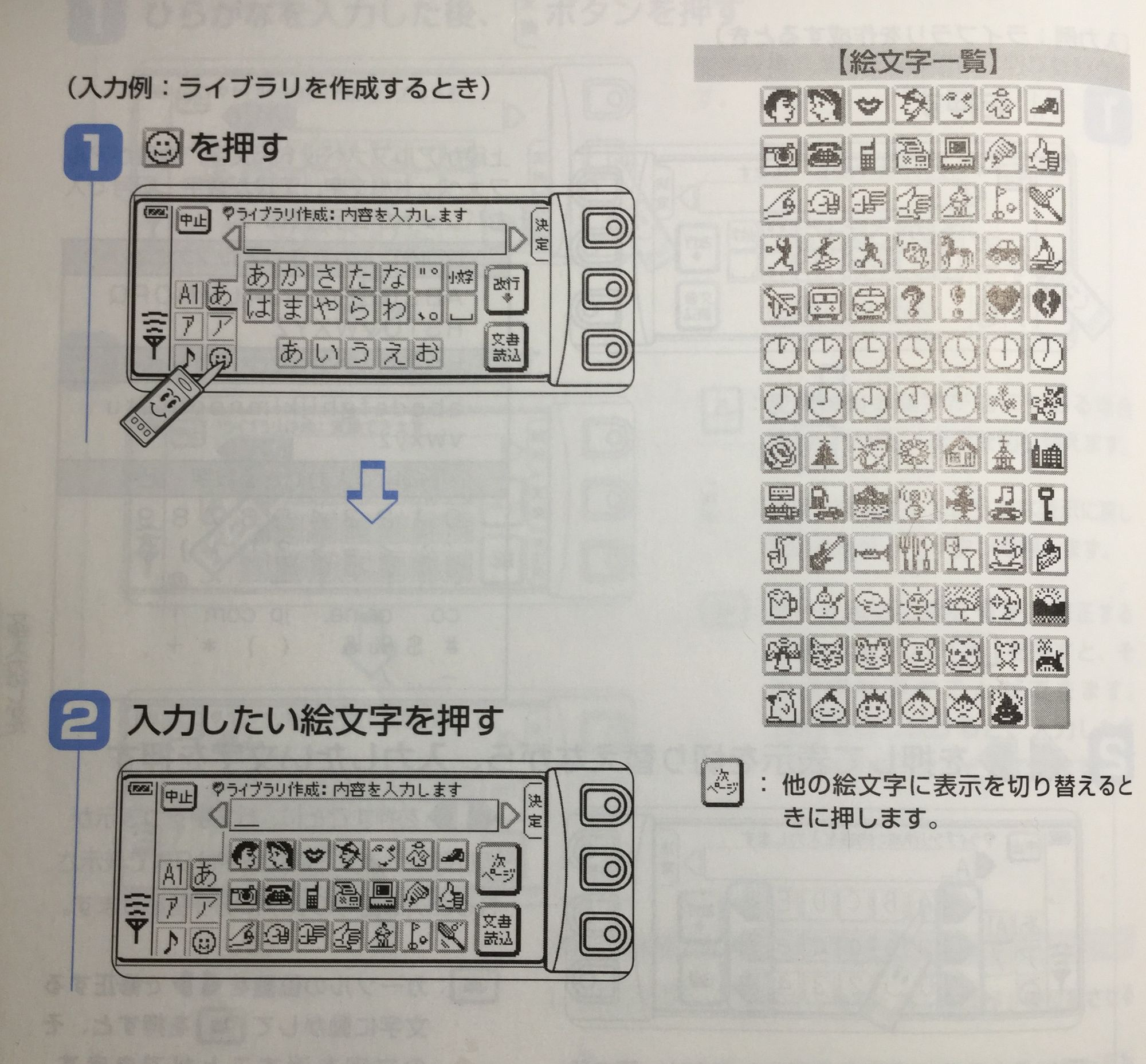

Keith Houston: "Yeah, a lot of that came from Matt Sephton’s work. He uncovered proto-emoji from as early as the mid-80s: images in Japanese word processors and PDAs that look like full emoji sets. Japan, with its complex scripts, needed specialized devices for typing, and these often included pictographic symbols. In some ways, the modern emoji family tree starts with these."

Keith Broni: "And then, of course, there was the heart symbol on pagers in 1995, often cited as the “first emoji”, though it wasn’t called that yet."

Keith Houston: "Right. It’s clear now that Japan had a cultural and technical infrastructure ready for emoji well before 1999. Meanwhile, in the West, we had emoticons and some weird symbolic characters in computer fonts like Wingdings or Dingbats: little snakes, UFOs, and card suits embedded in code sets meant for games."

The Japanese Emoji Sets (1997 - 2010)

The foundational emoji sets emerged in Japan in the late 1990s, but the real story is more complex than often reported.

Keith Houston: “The canonical story always started with Docomo’s 1999 emoji set, designed by Shigetaka Kurita. But newer research has shown it goes back further. The SoftBank set from 1997 predates Kurita’s work.”

Keith Broni: “Exactly. The myth that Shigetaka Kurita invented emoji persists, even though there’s evidence that the SoftBank (then J-Phone) set came first. Jeremy Burge’s article from 2019 aimed to correct the record, referencing Mariko Kosaka’s 2016 research that documented the 1997 SoftBank set. We now know that Kurita’s set wasn’t the first, though it certainly was influential.”

Keith Houston: “Kurita himself even acknowledged that a heart symbol was already present on pagers. So 1995 becomes this kind of proto-root for modern emoji. But the 1997 SoftBank set was on a mobile phone, not a pager or PDA, which makes it feel more aligned with how we use emoji today.”

日本のモバイル端末における絵文字はポケベルが最初ですが、ケータイに関しては私が開発したドコモの絵文字が最初ではなく、J-PHONEのパイオニアDP-211SWが最初だったと思います。#平成ネット史 #emoji

— くりたしげたか(to i)🌰ニコニコ代表の人 (@sigekun) January 3, 2019

Keith Broni: “That’s one key distinction: the SoftBank set being on a phone feels more modern, more connected to our current usage patterns. But there’s also something important from a linguistic point of view: the word ‘emoji’ actually appears in the 1997 J-Phone manual. That’s the first confirmed use of the term itself to describe these characters. So we’re talking not just about design and timing, but about the origin of the word too. But even with all this new documentation, it’s understandable why Kurita is so often cited. People love a single name and a clear origin story. His emoji set was the one that gained traction and set the tone for future development, even if it wasn’t the literal first.”

Keith Houston: “And that traction matters. You need someone to connect the dots between emerging technology and cultural moment, and that’s what Kurita and Docomo did.”

Kurita’s set, designed for Docomo’s i-mode service, became iconic. With just 176 characters, it included now-familiar symbols like hearts, suns, and umbrellas. Kurita aimed to enrich communication via short text messages on early mobile networks.

- Emoji Creation Story (July 2016)

- The Original iPhone Emoji Keyboard (February 2018)

- Correcting the Record on the First Emoji Set (March 2019)

- Apple's Emoji Evolution 1997—2018 (March 2019)

- Docomo Emoji Set To Be Officially Discontinued (May 2025)

Graphic Emoticons (1999 - 2010)

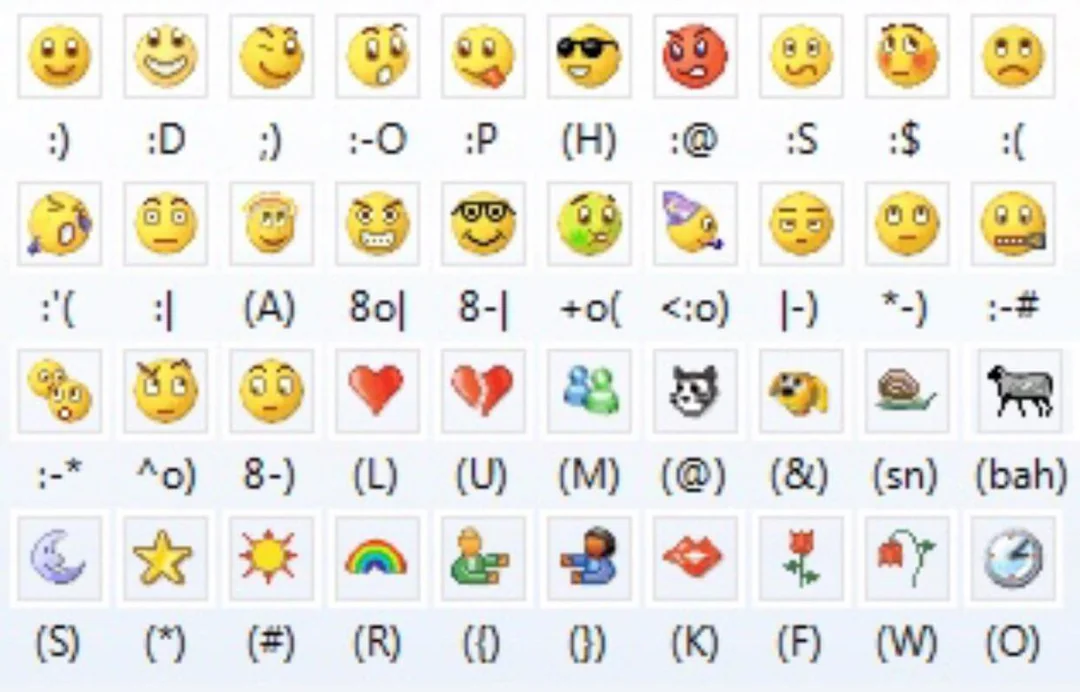

While Japan led the way with standardized emoji sets, Western internet culture had its own parallel evolution: the rise of graphical emoticons on messaging platforms like ICQ, MSN Messenger, and AOL Instant Messenger.

Keith Broni: "Of course, the West wasn’t unfamiliar with visual communication. We had AOL, MSN, ICQ: full of graphic emoticons."

Keith Houston: "Yeah, those apps leaned heavily on the yellow smiley aesthetic, rooted in the 1960s Harvey Ball design. They weren’t emojis per se, but they normalized graphical emotion indicators. You can see the convergence later when the Japanese and Western styles blend, especially when Apple adopts emoji."

Unicode First Steps In (2008 - 2012)

By the late 2000s, emoji had become a cultural and commercial success in Japan, but remained siloed within national carrier systems.

The fragmented nature of emoji sets across Docomo, SoftBank, and AU by KDDI posed a problem for global compatibility. That’s where the Unicode Consortium entered the picture, albeit reluctantly.

Keith Broni: “It’s definitely the case that Unicode underestimated the popularity of emoji when they were first introduced. They were essentially caving to pressure from Apple and Google.”

Unicode, a nonprofit organization responsible for maintaining global text standards, had historically focused on alphabetic and ideographic scripts. But around 2009–2010, Apple and Google began pushing for a unified emoji standard so these characters could work seamlessly across platforms and countries.

Google’s Mark Davis, also co-founder and then-president of Unicode, spearheaded one of the first major proposals to encode emoji.

Keith Houston: “It’s quite interesting. You had a proposal coming from inside Google, signed by the president of Unicode. If you're on the Unicode Technical Committee, how do you say no to that?”

At the time, the Unicode Consortium expected emoji to be a one-off endeavor.

Keith Houston: “They discovered they already had a hundred characters that were basically emoji. Just by accident, really. So they retroactively labeled them as emoji and added more on top.”

Keith Broni: “They wanted to wipe their hands of it and walk away. I’m pretty sure Mark Davis would say that himself. The idea was: we’ll encode these symbols to solve a short-term problem for Apple and Google, and that’ll be that.”

But things didn’t go according to plan. Emoji keyboards, initially hidden in iOS and Android for the Japanese market, were quickly unlocked by users worldwide using third-party apps. It became clear there was massive global demand for emoji, even outside Japan.

In retrospect, what began as a reluctant technical accommodation became one of the most impactful standardization decisions in the Internet’s history. Unicode had inadvertently become the governing body of a new, globally adopted visual language.

- Mark Davis on The Emojipedai Emoji Wrap Podcast (August 2016)

- Unicode: Behind the Curtain (April 2017)

- Meet the new Chair of the Unicode Emoji Subcommittee (December 2020)

Emoji Popularity Explodes & Representation Matters (2014-2019)

Following Unicode’s initial emoji standardization in 2010, the use of emoji began to surge globally. But it was around 2014 that emoji truly exploded into mainstream cultural consciousness. This was the tipping point when emoji stopped being seen as a novelty and started being treated as a serious, if playful, form of communication, and, inevitably, as a battleground for questions of representation and inclusion.

Keith Houston: “2014 is when I mark emoji as having really taken off. That’s when media outlets beyond tech blogs started covering them. Emojis weren’t just a digital curiosity anymore: they were a cultural artifact.”

The increased visibility of emoji sparked scrutiny about what, and who, was missing. Early emojis were overwhelmingly yellow, male-coded, and lacking in cultural diversity. People began asking: Where are the women in professions? Why are all the hands yellow? Why are there so few characters that represent people with disabilities?

Keith Broni: “The initial criticism came around skin tone representation and a bit around gender representation. Once emojis entered the mainstream, the gaps became obvious. And people didn’t just complain, they demanded change.”

Unicode found itself on the back foot. In the years that followed, they issued multiple major emoji releases to address the outcry.

Skin tone modifiers were introduced in 2015 using the Fitzpatrick scale, allowing five additional skin tones to be applied to human emoji. Gendered pairs followed soon after, allowing both male and female representations for professions, athletes, and roles.

Keith Houston: “There was suddenly this really busy three- or four-year period where every Unicode release was tackling representation. It’s not just male/female: there are hair types, skin tones, and disability symbols. It was like, how do we make this global keyboard more truly global?”

Still, Unicode’s central role as the emoji gatekeeper meant every decision about representation carried enormous symbolic weight. What was once a quiet standards body had, by accident, become the global arbiter of digital identity.

Keith Houston: “They were stuck managing not just characters, but the politics of visual language. And that’s a very different job.”

- 2015: The Year of Emoji Diversity (November 2014)

- The Trouble With Redheads (April 2015)

- Unicode and the Emoji Gender Gap (May 2016)

- Emoji ZWJ Sequences: Three Letters, Many Possibilities (July 2016)

- Gendered Emojis Coming In 2016 (July 2016)

Convergence, Formalization & Further Representation (2018 - 2023)

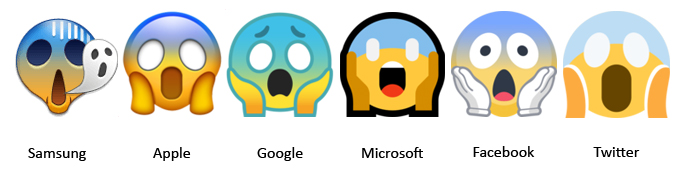

As emoji usage soared in the mid-2010s, it became clear that standardization of Unicode characters alone wasn’t enough: there was a growing need for visual standardization as well. While Unicode dictated which emoji should exist and what they represented conceptually, it did not control how each platform rendered them.

This creative freedom led to significant design discrepancies between vendors like Apple, Google, Samsung, and Microsoft, some of which caused serious miscommunication.

Keith Broni: “Each platform had to create their own emoji images to embed in their fonts, and while Apple was very consistent, you see the Apple set no matter where you are in their ecosystem. Others, like Samsung, were all over the place. Their early designs were wildly different.”

Samsung’s emoji set was particularly infamous for its idiosyncratic interpretations. Emojis that conveyed sarcasm or annoyance on one platform looked cheerful or flirtatious on another. The result was a fragmented semantic landscape, where users could send a message with one intent and have it received entirely differently.

Keith Broni: “I knew people who genuinely experienced communication breakdowns because of Samsung’s designs. I wrote my very first blog post for Emojipedia about how Samsung changed the rolling eyes emoji, it went from looking smug to exasperated. That shift changed how people understood the message.”

The most high-profile example of this problem was the gun emoji controversy. Originally, most platforms depicted the “🔫 Pistol” emoji as a realistic firearm. But in 2016, Apple unilaterally redesigned it as a bright green water pistol. Other vendors followed suit in the years that followed, but not without hesitation, and not simultaneously.

Keith Houston: “Apple’s decision changed the meaning of the emoji entirely. What used to look like a weapon became a toy. But for a while, some platforms still showed a real gun. So people were sending what they thought was playful imagery, and others saw threats. That’s not just aesthetic divergence, that’s a semantic incompatibility.”

Keith Broni: “And this was happening at a time when people in the U.S. had been arrested for using the gun emoji in threatening messages. Apple had a massive U.S. market share and was getting pressure over gun violence and messaging. The decision made sense socially, but it was disruptive technically.”

Unicode found itself in an awkward position. It defines emoji titles and provides sample illustrations, but ultimately leaves visual rendering up to vendors. This is intentional: just as Unicode didn't technically tell type designers how a letter “A” should look, it doesn’t mandate how the “face with rolling eyes” or “pistol” should appear. But with emoji, which have a single visible rendering on most platforms and are often interpreted literally, that hands-off approach caused serious inconsistencies.

Keith Houston: “It’s like Unicode saying, ‘Here’s what the letter A is,’ but every font shows it differently, except with emoji, it’s not a stylistic difference. Its meaning. When millions of people see only one rendering of an emoji, it effectively becomes the meaning.”

Other examples abounded: Apple’s once attempted to redesign the Peach emoji to be less butt-like, and this sparked considerable user backlash. Google moved the cheese on its hamburger emoji underneath the patty, outraging thousands. These seemingly small choices revealed just how loaded emoji design had become.

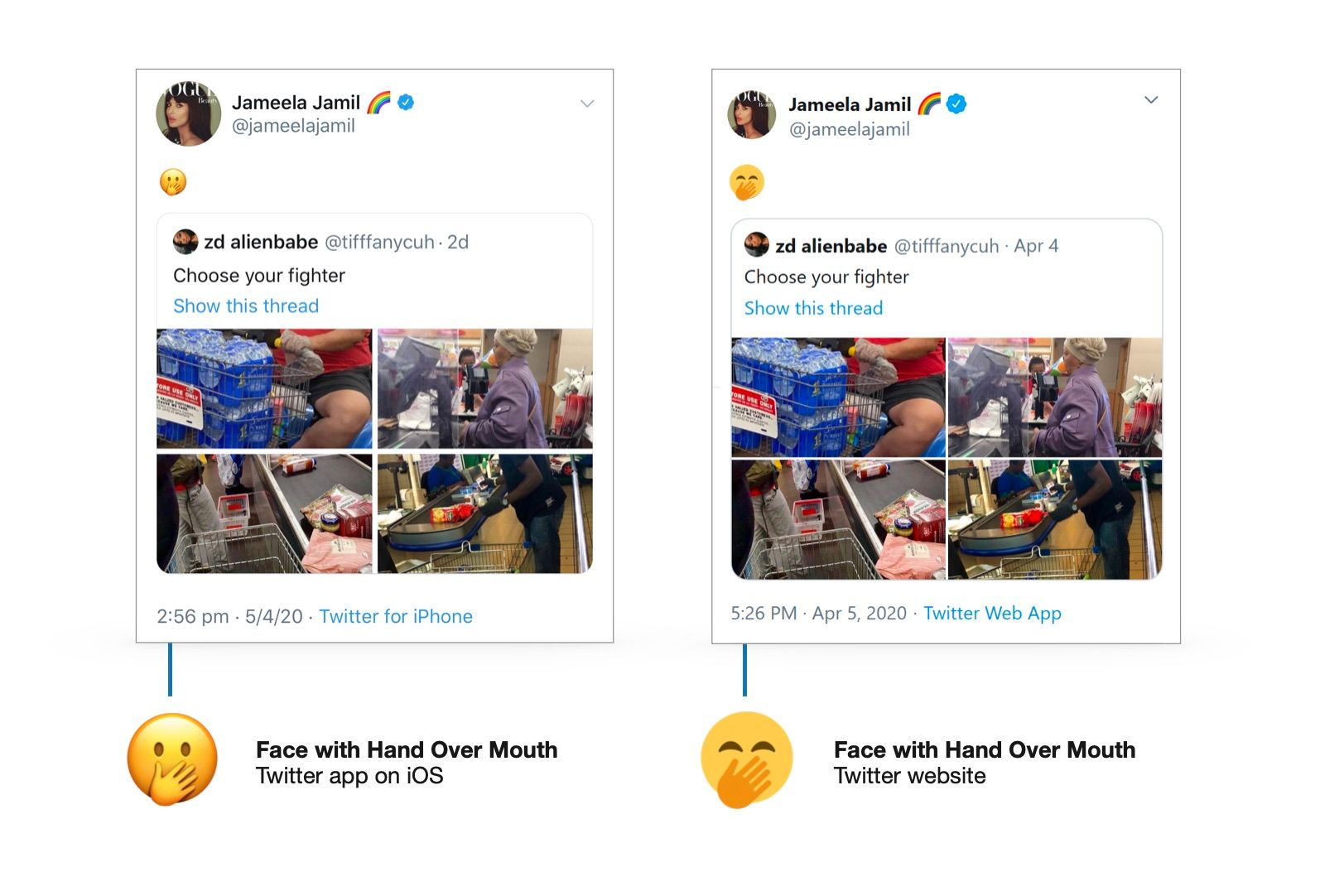

Keith Broni: “The peach, the burger, even the face with hand over mouth: all of them caused real stirrings. That last one was especially notable. Different platforms showed different facial expressions, so Unicode eventually added a second version to standardize the eye shape.”

These controversies underscored that emojis were no longer just icons. They were part of a dynamic, interpreted language. When design differs, meaning changes,and when meaning changes, communication falters. As a result, the convergence of emoji design became as important as their conceptual inclusion.

Keith Houston: “Courts are even considering not just what emoji were used, but which application they were sent from, and how they rendered on both ends. That’s wild, but it shows how significant these semantic mismatches can be.”

In response to the chaos, many vendors have gradually aligned their designs. But the era of platform divergence left a lasting mark on how users view emoji: not just as symbols, but as ambiguous, interpretable, and deeply contextual linguistic tools.

- Apple And The Gun Emoji (April 2016)

- Samsung's Emoji Adventures (September 2017)

- How Do You Like Your Burger Emoji? (October 2017)

- Samsung Experience 9.0 Emoji Changelog (February 2018)

- 2018: The Year of Emoji Convergence? (February 2018)

- Apple Proposes New Accessibility Emojis (March 2018)

- All Major Vendors Commit to Gun Redesign (April 2018)

- Google's Three Gender Emoji Future (March 2019)

- Unicode Brings Forward Gender Neutral Timeline (October 2019)

- X Redesigns Water Pistol Emoji Back To A Firearm (July 2024)

The Stickers, AI, & The Future Of Emoji Creation (2023 onwards)

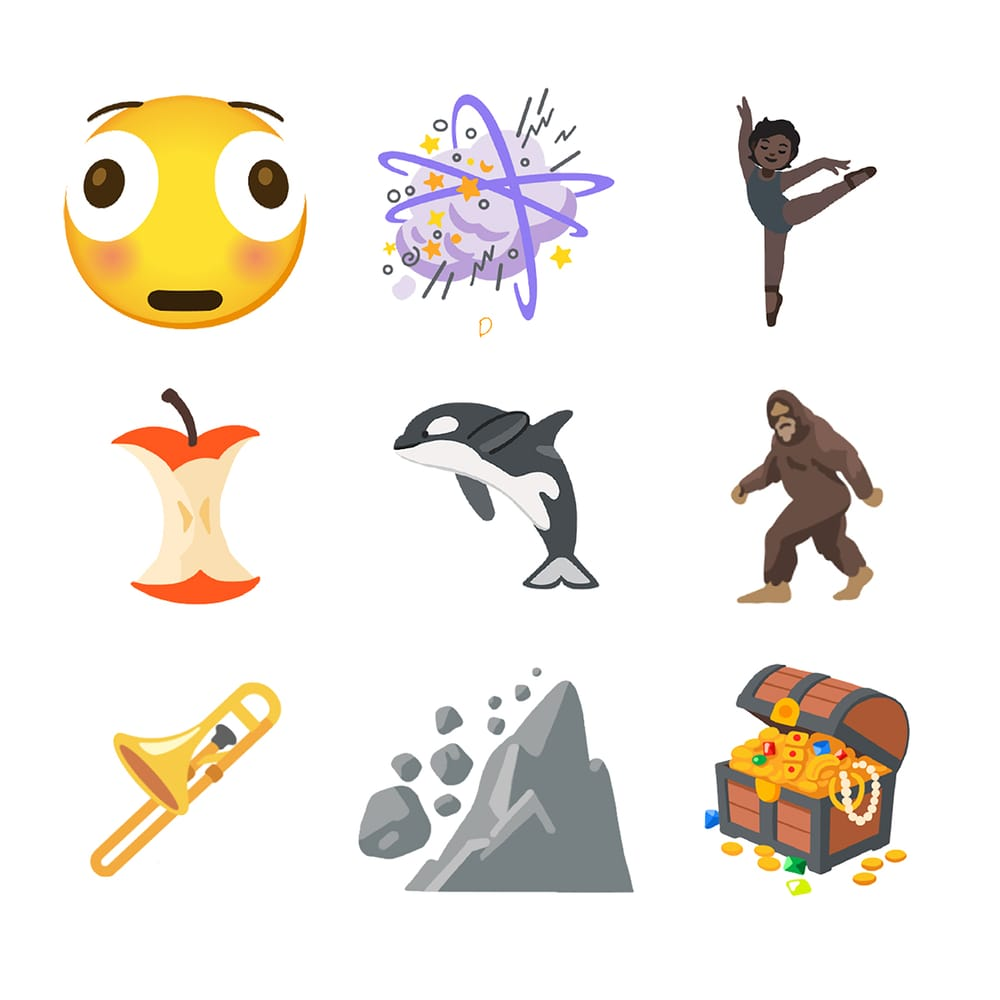

As emojis matured into a fully integrated part of digital communication, their rate of expansion began to slow. Unicode, once racing to meet global demand for new emoji concepts, has become more selective. Meanwhile, user expectations continue to evolve, shaped by advances in generative AI, platform-specific sticker tools, and a growing desire for customization.

Keith Broni: “Emoji 17.0 is expected to include around 14 new concepts. The rest are combinations: people with bunny ears, two wrestlers in different pairings. That’s a huge drop from earlier years, where dozens of unique emojis were added at once.”

This shift is both a technical and strategic one. The Unicode Consortium was never intended to act as a global emoji design bureau. Its mission is to encode the world’s written languages, not to manage pop culture iconography. For over a decade, though, the explosion of emoji forced Unicode to do just that.

Keith Houston: “They’ve tried to get out of the emoji game multiple times. There’s the CHAI proposal, standardized image embedding, and the Wikidata QID idea, which suggests concepts could be emojis without Unicode needing to approve each one. But nothing’s stuck yet.”

Despite these efforts, Unicode remains the gatekeeper for what qualifies as a standardized emoji. But parallel systems are emerging and fast. Apple’s Genmoji, introduced in iOS 18, lets users generate customized emoji-style stickers using AI. These images can be sent inline with text messages, mimicking the experience of sending Unicode emoji.

Keith Broni: “Apple’s image embedding protocol means stickers can now appear inline with text and scale with font size. From the user’s perspective, it feels just like using emoji. But technically, it’s not character-based, it’s image-based.”

This change is subtle but transformative. If other major players like Google, Microsoft, and Samsung adopt a similar embedding standard, emoji could expand beyond the Unicode set into a new era of freeform, AI-generated expression. Already, Samsung is reportedly developing a Genmoji competitor, and Google's Emoji Kitchen and allows users to combine emojis into unique sticker hybrids.

Keith Broni: “Emoji Kitchen is a great example. It’s not AI-driven, it’s curated by Google’s team, but people use it constantly. We’re seeing clear demand for customization in the middle tier of emoji: objects, foods, and animals. Not the top 5% of emojis like red heart or tears of joy, which dominate usage, but the long tail.”

This long tail is precisely where AI may flourish. Users could generate a white wine glass emoji instead of the standard red, or depict their specific dog breed instead of a generic 🐶 Dog Face. While Unicode-approved emoji will likely remain the backbone of quick, universal expression, AI tools are poised to satisfy more personal and niche needs.

Keith Houston: “But here’s the tension. Emoji work because they’re constrained. You’re taking an ineffable idea and compressing it into one of a few hundred images. That constraint forces creativity. If AI gives you exactly what you want every time, it might lose that shared cultural power.”

Keith Broni: “Still, the technology is evolving fast. Apple’s current Genmoji are in beta, but their latest update mimics Google's Emoji Kitchen by letting users choose multiple emojis as input. That dramatically improves expressiveness.”

AI art models are improving rapidly, and tech companies are exploring how best to fuse user input, design consistency, and cross-platform compatibility. For now, Apple and Google’s experiments are still limited to their own ecosystems, but a shared standard could upend the entire Unicode-centric model.

Keith Broni: “We’re potentially on the verge of a paradigm shift. If platforms standardize image-based emoji delivery across ecosystems, users could generate and share custom emoji just as easily as they do with Unicode characters today. That being said, the top emojis, the red heart, the laughing face, are too embedded to be replaced. They’re free, universal, and familiar. That’s powerful.”

Keith Houston: “Exactly. Emojis have become the digital equivalent of punctuation. They’re not just visual flair: they’re essential grammar. And that’s why, even as the format evolves, emoji as a concept will remain core to how we communicate.”

- iOS 13 Adds Memoji to Emoji Keyboard (September 2019)

- Draft Emoji List for 2025/2026 Revealed (November 2024)

- Hands-On With Apple's Genmoji AI Emoji Generator (October 2024)

- Emojipedia's New, Free-To-Use AI Emoji Generator (December 2024)

- Genmoji Creatures Roam Free Following iOS 18.2 Release (December 2024)

- Hands On With iOS 26's Genmoji Mixes (June 2025)