What Is An Emoji In 2025?

At Emojipedia, there are no silly questions. Not “Why am I seeing so many 🚡 Aerial Tramway emojis on TikTok?” Or “What does this 👁️👄👁️ mean, and should I be scared?” Or even “What actually is an emoji?”

At Emojipedia, there are no silly questions. Not “Why am I seeing so many 🚡 Aerial Tramway emojis on TikTok?” Or “What does this 👁️👄👁️ mean, and should I be scared?” Or even “What actually is an emoji?”

Maybe your first thought is, “Well, that’s easy. What else would emojis be but those miniature little pictures we can sprinkle into our internet conversations, slap onto digital graphics as decor, or these days even summon from the AI’s mercurial depths with a short prompt?”

Sure, some might say emojis are all of those things. But in an era flooded with digital imagery, pixelated potpourri, and AI-generated everything, it’s easy to forget: emoji hasn’t always meant the same thing.

Understanding how these pint-sized pictographs became global communication game-changers shows us how online self-expression has evolved in the digital age—and where it might go next.

So grab some 🍿 Popcorn—emoji or IRL—and let’s dive in.

👶🏻 FROM HUMBLE ORIGINS: BEFORE THERE WAS 🙂 THERE WAS :-)

Emojis didn’t just pop into our keyboards one day, all packaged up with a neat little bow. Their rise to global online ubiquity started with a simple need—to show emotion where plain text fell flat.

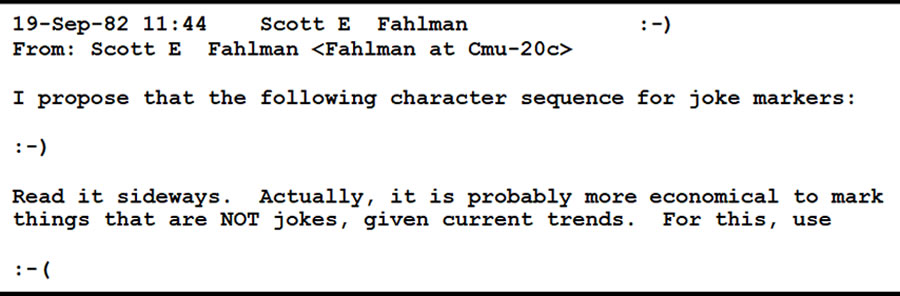

Enter Scott Fahlman. In 1982, he noticed people on Carnegie Mellon computer science bulletin boards didn’t have a way to distinguish jokes from serious posts.

He proposed a simple, subtle sideways smiley—:-)—and thus was engineered the OG proto-emoji: the emoticon. A new internet era had begun.

Soon came :-P or :P for goofiness, :'-( or :’( for crying, :-O or :O for surprise, and ;-) or ;) for flirty winks.

Emoticons—a blending of the words “emotion” and “icon”—quickly took hold across early chatrooms, forums, and social platforms of internet antiquity.

Meanwhile in Japan in 1986, a different approach soon emerged independently: kaomoji, made from full-width kana and box-drawing characters and punctuation.

They stood upright and packed nuance into the eyes—like (^_^;) for embarrassment, (@_@) for being awestruck, or this iconic figure (╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻) for all those irate table-flipping moments.

Even though emoticons and kaomoji, these text-based emoji ancestors, are certified internet relics, they’re still used today, whether for nostalgia or simplicity.

But remember—they were built from existing keyboard characters. No official status. Not emojis yet.

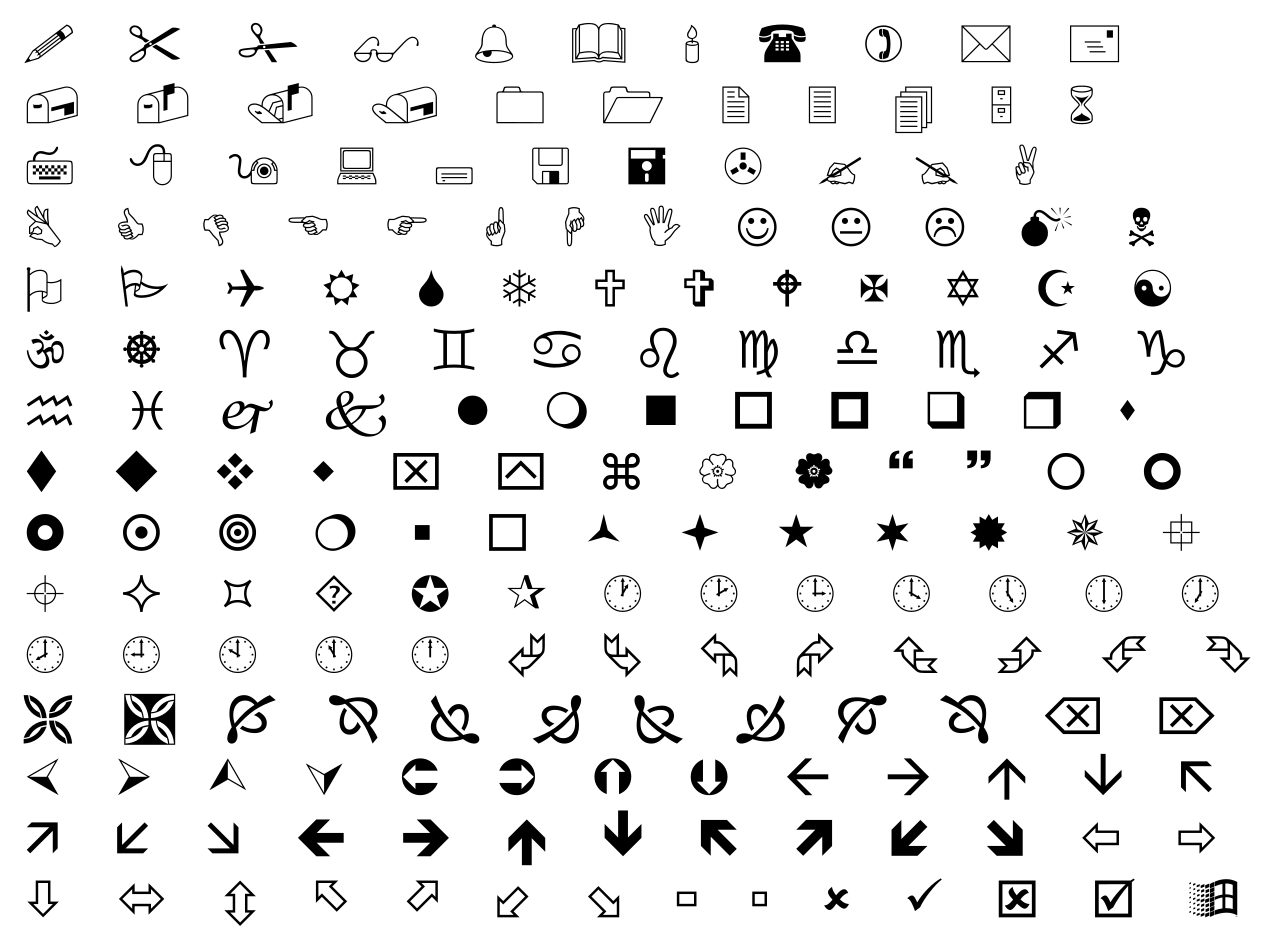

Then came Microsoft’s 1990s absurdist, almost dada-ist, dingbat font: Wingdings.

It mapped physical keyboard characters to custom glyphs.

And it showed that little images could be distributed through typefaces.

But because the pictographs themselves didn’t have their own codepoints (for example, the capital letter J represented a smiley face), they weren’t what we know today as emojis.

But we’re inching closer on the emoji timeline.

In the ‘80s and early ‘90s, Japanese PDAs began stashing tiny pixelated icons in “private-use areas.”

They only worked on matching hardware, but they laid the groundwork for embedded pictographs in mobile messages.

Then came the moment we’ve all been waiting for: the emergence of the emoji.

In 1999, designer Shigetaka Kurita created a set of nearly 200 12×12 pixel pictographs for the i-mode mobile internet service from Japanese carrier NTT Docomo.

Users could embed icons like a cat face, a sun, and a smiley in mobile messages—cross-device, cross-platform (within Docomo’s ecosystem).

But Kurita wasn’t actually first.

Japanese carrier SoftBank released a phone with 90 emojis in 1997—plus the first known printed use of the word “emoji” in its manual—from the Japanese e (絵, “picture”) + moji (文字, “character”).

So, Kurita popularized emojis; SoftBank beat him to it.

But the emojis of the late last millennium were a far cry in visual aesthetic and recognizability from the ones we know today.

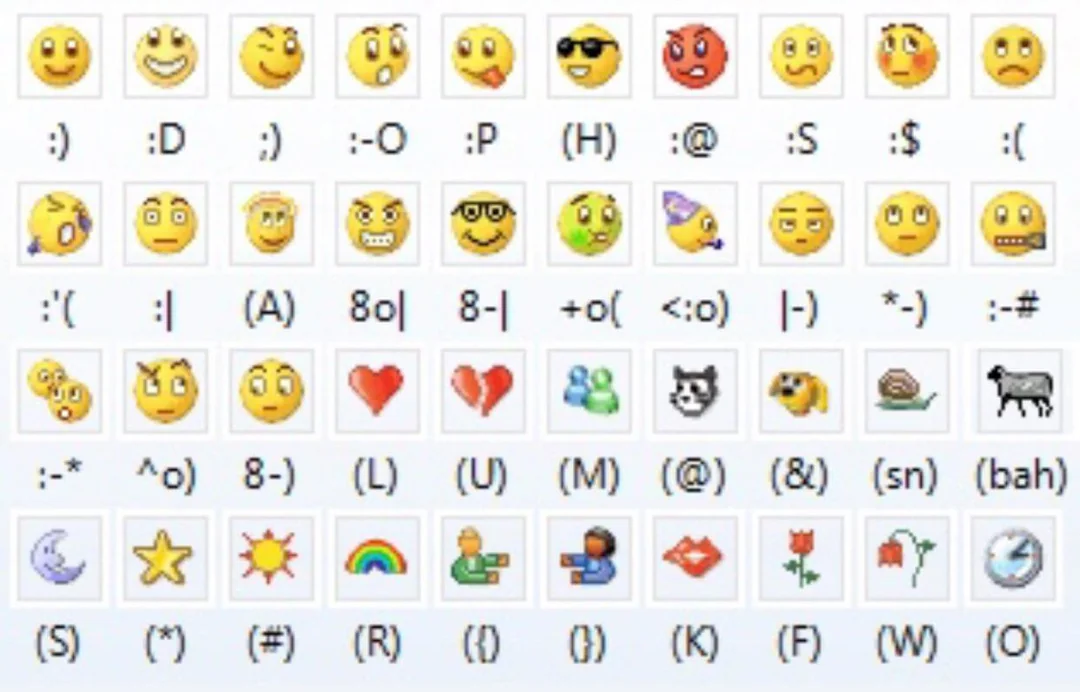

In the late ‘90s and into the early 2000s we started to see static or animated, pixelated graphic emoticons in instant messaging clients.

Typed into platforms like AIM or MSN Messenger, certain plain-text emoticon and non-emoticon shortcode strings like these would trigger local, platform-native graphic emoticons—ones that looked more like the emojis of today.

They weren’t Unicode-standardized—more on that soon—but they brought us closer in design, style, and function to the emojis we now know.

📖 UNICODE UNLEASHES EMOJI

We can’t think of modern emojis without acknowledging the framework architected by Unicode behind the scenes to bring them into being.

The Unicode Consortium defines the universal standard that assigns nearly every documented digital character—letters, numbers, and symbols, for example—a unique codepoint.

That lets them render and be read across different sites, devices, networks and operating systems.

By 2010, Unicode had more than 100,000 characters... but no emojis. Apple and Google began urging Unicode to fix that.

Some people at Unicode read the writing on the wall, and in October 2010, Unicode Version 6.0 arrived, with 722 new emoji codepoints assigned.

Now, emojis were searchable, copy-pasteable, accessible via system keyboards, embeddable in text, and, crucially, renderable cross-platform.

Each vendor, like Apple, Google, and Samsung for example, renders its own emoji designs.

So if you send the 🐱 Cat Face from iOS to Android, it’ll look different—kind of like a different font—but the code stays the same.

Unicode 6.0 introduced emoji hall-of-famers like the 😂 Face With Tears of Joy, the ✨ Sparkles, and the 💩 Pile of Poo (a 1997 SoftBank original).

Since then, Unicode has accepted thousands more proposals—not without a rigorous approval process—bringing today’s emoji count to nearly 4,000 out of over 150,000 total Unicode characters.

So, is Unicode still the final word on emoji, or is the landscape starting to shift?

🤔 IF IT LOOKS LIKE AN EMOJI…

Okay, so what exactly is an emoji, then? After all that, would you be mad if we said there’s no straightforward answer?

We’ve seen throughout emoji history the many efforts to popularize pictorial graphics, before and after Kurita’s legacy-leaving Docomo emoji set stuck in our popular consciousness.

And even now, emoji imposters and approximators abound. Perhaps more than ever. Welcome to the wide, wacky world of stickers.

You know them. Stickers are those larger emoji-esque images or graphics that can be dropped into internet conversations, usually with rich visuals, and often with animation and sound.

You’ve probably seen them in messages and keyboards of apps like Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. You might even have used them like emojis.

But with no Unicode approval or assigned codepoints, they technically can’t be classified as emojis—essentially just image files.

Stickers entered the scene around 2011 starting with the Japanese app LINE.

They exploded, especially since they served alongside emojis as alternatives that allowed much more flexibility and creativity—in who could create them and what they could look like.

It started to become commonplace to see branded, often paywalled, proprietary sticker packs and sets in the mid-2010s distributed as image keyboard apps—like Kimoji, Kim Kardashian’s 2015 app, MojiCam’s 3D avatar stickers, Futuremoji, and many more.

In 2017 and 2018 came Animoji and Memoji, respectively, Apple’s more advanced animated stickers with motion tracking in its quintessential emoji-style design.

Because these stickers had similar-sounding names and looked and behaved like Apple’s emojis—and sat right on the emoji keyboard—many users began to associate and sometimes confuse the two.

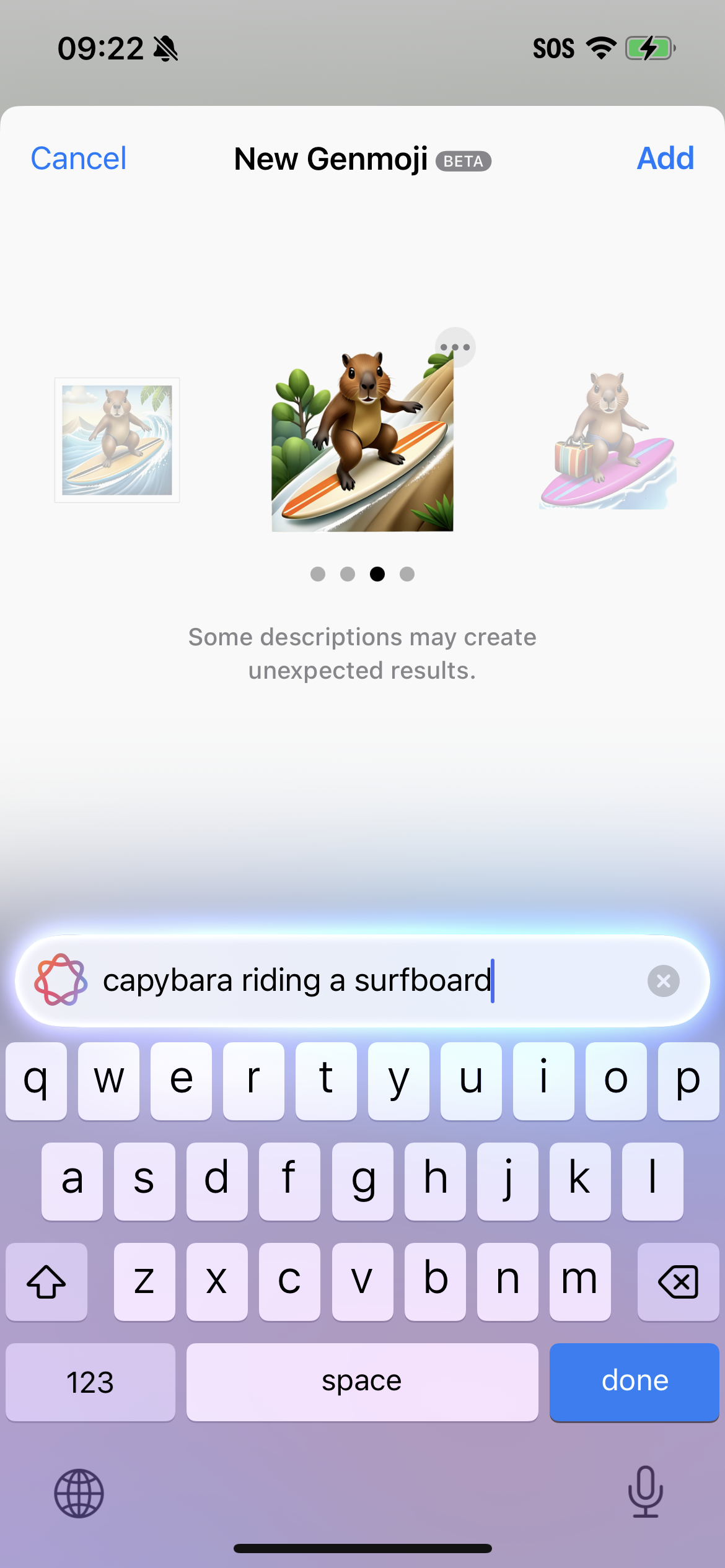

Then, in 2024, came Genmoji, Apple’s AI-generated emoji-style stickers, further blurring the line.

You type a prompt—“a capybara riding a surfboard”—and the Genmoji feature spits out a playful little image in Apple’s emoji design aesthetic.

Like all stickers, they’re not Unicode-approved and still export as images, not text. But they appear embedded in-line with messages, just like real emojis. So it can be easy to forget the difference.

It’s entirely possible that other major vendors like Google and Microsoft follow suit with their own similar emoji AI integrations for users—meaning the emoji landscape could shift yet again.

🔮 CONCLUSION: DID WE REACH A CONCLUSION?

There’s no shortage of stickers and creation tools that have arguably democratized the making of images that sorta, kinda feel like emojis. Their influence—and the rise of AI features—have arguably blurred the line of what counts as an emoji in our collective mind.

While these emoji-esque stickers serve similar functions, they don’t adhere to Unicode’s standards. But if enough of us agree to expand the definition of something, does the original meaning still hold?

Unicode defined emojis strictly: pictographs with codepoints in the Unicode Standard designed for global interoperability. Case closed. End of story.

But even though stickers, Animoji, and Genmoji, for example, don’t meet Unicode’s criteria, they feel like emojis. And many function like emojis in iOS 18 onwards, embeddable in-line with text within many areas across the Apple ecosystem.

So is it possible the definition of emoji could expand to encompass something beyond those boundaries? Or are we sticking with the same standards from 15 years ago in a digital world that’s unfolding at fiber-optic speed?

So we look ahead without a definitive answer. But one thing’s for sure: if emojis have taught us anything, it’s that how we express ourselves is always evolving, expanding, remixing, and being redefined, and maybe that’s the whole point.